ISSUE1678

- Mark Abramowicz, M.D., President has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Jean-Marie Pflomm, Pharm.D., Editor in Chief has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Brinda M. Shah, Pharm.D., Consulting Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Michael Viscusi, Pharm.D., Associate Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Explain the current approach to the management of migraine.

- Discuss the pharmacologic options available for acute and preventive treatment of migraine and compare them based on their efficacy, dosage and administration, potential adverse effects, and drug interactions.

- Determine the most appropriate therapy given the individual presentation of a patient with migraine.

Acute Treatment

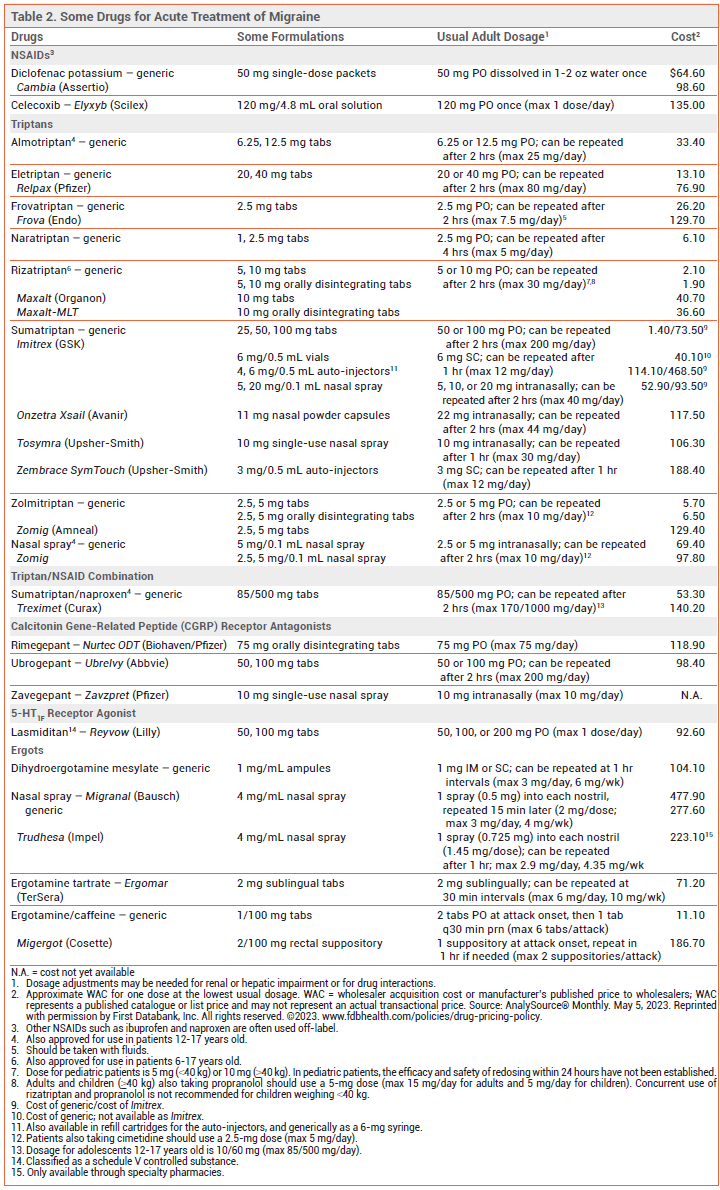

- An oral nonopioid analgesic is often sufficient for treatment of mild to moderate migraine pain.

- Use of butalbital- or opioid-containing products for migraine treatment is not recommended.

- A triptan is the drug of choice for moderate to severe migraine pain in most patients without vascular disease.

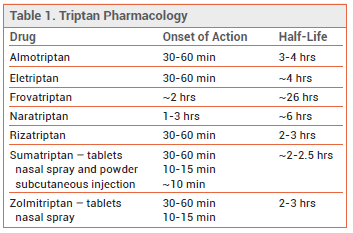

- The shorter-acting oral triptans sumatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, rizatriptan, and zolmitriptan are similar in efficacy, speed of onset, and duration of action.

- Intranasal triptan formulations are faster-acting than oral triptans. Subcutaneous sumatriptan is the most effective triptan formulation, but it causes the most adverse effects.

- CGRP receptor antagonists and the 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan appear to be less effective than triptans, but they can be used in patients with vascular disease.

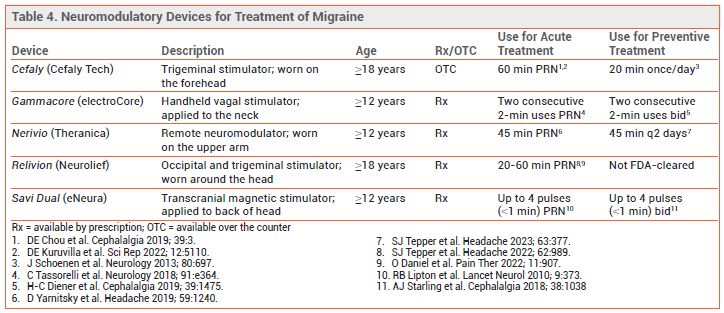

- A neuromodulatory device can be tried when pharmacotherapy cannot be used.

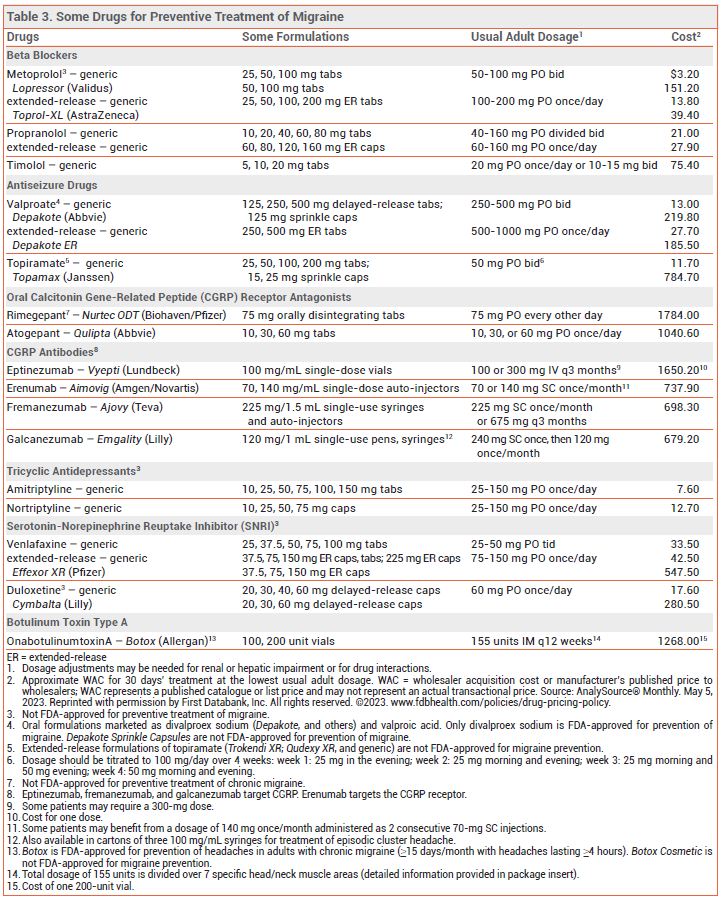

- Beta blockers and the antiseizure drugs topiramate and valproate are effective for preventive treatment of migraine, but they may be difficult to tolerate.

- CGRP antagonists are effective, but expensive. A CGRP monoclonal antibody can be effective when other drugs have failed.

- Pericranial onabotulinumtoxinA injections can be used in adults with severe chronic migraine.

- Nonpharmacologic options include neuromodulatory devices, behavioral therapy, and acupuncture.

An oral nonopioid analgesic is often sufficient for acute treatment of mild to moderate migraine pain without severe nausea or vomiting. A triptan is the drug of choice for treatment of moderate to severe migraine in most patients without vascular disease.1 Treatment of pain when it is still mild to moderate in intensity improves headache response and reduces the risk of recurrence.

ANALGESICS — Aspirin and acetaminophen, used alone, together, or combination with caffeine, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in relieving mild to moderate migraine pain.2-4 The NSAID diclofenac is available in a powder for oral solution (Cambia) for treatment of migraine; it has a rapid onset of action (~15 minutes).5

Products that contain butalbital or an opioid are not recommended for acute treatment of migraine. There is limited evidence that butalbital is effective in relieving migraine pain. Opioids can be effective, but they can cause serious adverse effects. Regular use of butalbital- or opioid-containing analgesics can lead to medication overuse headache, tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

Pregnancy – Occasional use of acetaminophen during pregnancy is generally considered safe.6 Use of NSAIDs during the third trimester may cause premature closure of the ductus arteriosus and persistent pulmonary hypertension in the neonate, but these effects appear to be uncommon if the drug is stopped 6-8 weeks before delivery.

TRIPTANS — The shorter-acting oral 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists (triptans) sumatriptan, almotriptan, eletriptan, rizatriptan, and zolmitriptan are similar in efficacy (placebo-corrected 2-hour headache response rates of ~30-50% with maximum initial doses). The longer-acting oral triptans naratriptan and frovatriptan are generally better tolerated than shorter-acting triptans, but they have a slower onset of action and lower initial response rates. Patients who do not respond to one triptan may respond to another. An oral fixed-dose combination of sumatriptan and naproxen (Treximet, and generics) has been more effective in relieving moderate or severe migraine than either of its components alone.7

Intranasal and injectable triptan formulations are faster-acting than oral tablets. Subcutaneously administered sumatriptan relieves pain faster and more effectively than oral triptan formulations, but it causes more adverse effects.8

Recurrence – Moderate to severe migraine recurs within 24 hours after treatment with a triptan in ~20-40% of cases. Early treatment of an attack reduces recurrence rates. Recurrences may respond to a second dose of the triptan.

Adverse Effects – Triptans can cause tingling, flushing, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, and a feeling of heaviness or tightness in the chest. Subcutaneous sumatriptan can cause injection-site discomfort. Intranasal triptan formulations can leave an unpleasant aftertaste. CNS symptoms such as somnolence and weakness are commonly reported following triptan therapy, but they may be part of the migraine attack, unmasked by the successful treatment of pain, rather than adverse effects of the drug. Use of triptans for ≥10 days per month can cause medication overuse headache. Sumatriptan and naratriptan are contraindicated for use in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Naratriptan is also contraindicated for use in patients with severe renal impairment.

Angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, seizures, and death have occurred very rarely with use of triptans.9 All triptans are contraindicated for use in patients with ischemic or vasospastic coronary artery disease, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, ischemic bowel disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or a history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, or hemiplegic or basilar migraine. They should be used with caution in patients with other significant risk factors for vascular disease, particularly diabetes.

Drug Interactions – Triptans should not be used within 24 hours of another triptan or an ergot because vasoconstriction could be additive. Concurrent use of monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and triptans can result in additive serotonergic effects. Use of sumatriptan, rizatriptan, or zolmitriptan within 2 weeks after an MAO-A inhibitor can result in increased triptan serum concentrations and is contraindicated. Propranolol increases serum concentrations of rizatriptan. Cimetidine increases serum concentrations of zolmitriptan. Inhibitors of CYP3A4 can increase serum concentrations of almotriptan and eletriptan; use of eletriptan is contraindicated within 72 hours after taking a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.10 Serotonin syndrome has been reported with concurrent use of triptans and serotonin reuptake inhibitors, but data from large observational studies suggest that the risk is low.11

Pregnancy and Lactation – In a population study in Norway, there was no association between triptan use during pregnancy and birth defects.12 Levels of sumatriptan and eletriptan in breast milk are low and are not expected to cause adverse effects in most breastfed infants.13

View the Comparison Table: Triptans for Migraine

CGRP RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS — Three smallmolecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists are FDA-approved for acute treatment of migraine in adults: rimegepant (Nurtec ODT) and ubrogepant (Ubrelvy) are taken orally,14,15 and zavegepant (Zavzpret) is available as a nasal spray.16 In clinical trials, about 10% more patients were free of headache 2 hours post-dose with these drugs compared to placebo.17-19

The onset of pain relief appears to occur sooner with zavegepant than with rimegepant or ubrogepant (~15 vs ~60 minutes). The half-life of rimegepant (~11 hours) is longer than that of ubrogepant (5-7 hours) or zavegepant (~6.5 hours). No trials directly comparing these drugs with each other or with triptans are available. CGRP receptor antagonists appear to be less effective than triptans, but they can be used in patients with vascular disease and do not cause medication overuse headache.20

Adverse Effects – Systemic adverse effects are uncommon with use of CGRP receptor antagonists. Nausea, somnolence, and (rarely) hypersensitivity reactions can occur. Zavegepant can cause dysgeusia, ageusia, and nasal discomfort.

Drug Interactions – Ubrogepant and rimegepant are substrates of CYP3A4, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). Concurrent use of these drugs with strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 or with inhibitors of P-gp or BCRP should be avoided.10

Zavegepant is a substrate of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3) and sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP); its use with inhibitors or inducers of these transporters should be avoided. Intranasal decongestants can decrease zavegepant absorption; concurrent use should be avoided.

Pregnancy and Lactation – Rimegepant, ubrogepant, and zavegepant have not been adequately studied in pregnant women. Levels of rimegepant in breast milk are low; ubrogepant and zavegepant are also likely to be minimally secreted into breast milk because they are highly protein-bound.21,22

SELECTIVE 5-HT1F RECEPTOR AGONIST — Lasmiditan (Reyvow) selectively binds to 5-HT1F receptors expressed on trigeminal neurons, inhibiting pain pathways in the trigeminal system. In clinical trials, the rate of freedom from headache 2 hours post-dose was modestly higher with lasmiditan (~30%) than with placebo (15-20%).14,17 Lasmiditan appears to be less effective than triptans, but it can be used in patients with vascular disease.20

Adverse Effects – Lasmiditan can cause CNS adverse effects including dizziness, paresthesia, sedation, vertigo, incoordination, cognitive changes, and confusion. Fatigue, nausea and vomiting, muscle weakness, lethargy, palpitations, increases in blood pressure, decreases in heart rate, reactions consistent with serotonin syndrome, and hypersensitivity reactions, including angioedema and rash, have also been reported. Like triptans, lasmiditan can cause medication overuse headache.

Lasmiditan can decrease wakefulness and impair driving ability. The lasmiditan labeling warns against driving or operating machinery for at least 8 hours after taking the drug. Lasmiditan is classified as a schedule V controlled substance.

Drug Interactions – Use of lasmiditan with alcohol or other CNS depressants could result in additive effects. Coadministration of lasmiditan with serotonergic drugs may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome. Lasmiditan should be used with caution in patients who are taking other heart rate-lowering drugs. Lasmiditan inhibits P-gp and BCRP; coadministration with P-gp or BCRP substrates should be avoided.10

Pregnancy and Lactation – No data on the use of lasmiditan in pregnant or breastfeeding women are available. Lasmiditan and its metabolites have been detected in the milk of lactating rats.

ERGOTS — A fixed-dose combination of ergotamine tartrate, a nonspecific serotonin agonist and vasoconstrictor, and caffeine is available in tablets and suppositories for acute treatment of moderate to severe migraine. The combination is less effective than a triptan.23

Dihydroergotamine can be effective in some patients whose migraine headaches do not respond to triptans.17 It is available parenterally and as a nasal spray (Migranal, and generics; Trudhesa). In clinical trials, Migranal relieved migraine pain after 2 hours in ~30-60% of patients.24 Systemic bioavailability is greater with Trudhesa than with Migranal; it requires only one spray per nostril rather than two to deliver a full dose.25

Adverse Effects – Dihydroergotamine is a weaker arterial vasoconstrictor than ergotamine and causes fewer serious adverse effects. Nausea and vomiting are common with ergotamine, but pretreatment with or concurrent use of an antiemetic drug such as metoclopramide can reduce GI adverse effects. Serious adverse effects, such as vascular occlusion and gangrene, are rare and are usually associated with overdosage (>6 mg in 24 hours or >10 mg per week). Hepatic impairment or fever can accelerate development of severe vasoconstriction. Ergots are contraindicated for use in patients with arterial disease or uncontrolled hypertension.

Drug Interactions – Concurrent use of ergots and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors is contraindicated.10 The effects of ergots can also be potentiated by triptans, beta blockers, dopamine, and nicotine. Trudhesa is contraindicated for use with peripheral and central vasoconstrictors. Ergots and triptans should not be taken within 24 hours of each other. Rarely, reactions consistent with serotonin syndrome have been observed when 5-HT1 agonists such as dihydroergotamine were coadministered with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Pregnancy and Lactation – Ergots can reduce placental blood flow and ergotamine is secreted into breast milk. Use of ergots in pregnant or breastfeeding women is contraindicated.

ANTIEMETICS — The dopamine receptor antagonists metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, chlorpromazine, and droperidol can reduce nausea and headache pain in patients with migraine.26 These drugs can cause extrapyramidal adverse effects and prolong the QT interval, increasing the risk of torsades de pointes.

MEDICATION OVERUSE HEADACHE — Overuse of drugs for acute treatment of migraine, especially butalbital and opioids but also triptans, lasmiditan, NSAIDs, and ergots, can lead to increased frequency and severity of headache with poor response to acute and preventive treatment. Treatment of medication overuse headache involves withdrawing the overused drug(s); abrupt withdrawal may require hospitalization and bridge therapy with other drugs. Preventive treatment for migraine should be considered, and some expert clinicians suggest limiting future acute migraine treatment to 2 days per week.27 CGRP receptor antagonists have not been associated with development of medication overuse headache.

DRUGS FOR PREVENTIVE TREATMENT

Indications for preventive treatment of migraine include frequent or severe attacks, a contraindication to or toxicity with acute treatments, and patient preference.1 Menstrual migraine can sometimes be prevented by taking an NSAID or a triptan (particularly frovatriptan) for several days before and after the onset of menstruation.28

BETA BLOCKERS — Propranolol and timolol are FDA-approved for preventive treatment of migraine, but metoprolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, and nadolol are also effective.

Adverse Effects – Beta blockers can worsen asthma symptoms and depression, and cause fatigue, exercise intolerance, sleep disorders, and orthostatic hypotension. They should not be used in patients with decompensated heart failure.

View the Comparison Table: Some Drugs for Migraine Prevention in Adults

ANTISEIZURE DRUGS — Valproate and topiramate are FDA-approved for migraine prevention. About 50% of patients achieve a ≥50% reduction in headache frequency with use of either drug.29 In double-blind trials, topiramate was at least as effective as propranolol for migraine prevention.30 Topiramate has reduced migraine frequency and symptoms in adults with ≥15 headache days/month for ≥3 months and in those with medication overuse headache.31

Adverse Effects – Valproate can cause nausea, fatigue, tremor, weight gain, and hair loss. Acute hepatic failure, pancreatitis, and hyperammonemia (in patients with urea cycle disorders) occur rarely. Polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, lipid abnormalities, hirsutism, and menstrual disturbances have also been reported.

Topiramate commonly causes paresthesias; fatigue, language and cognitive impairment, taste perversion, weight loss, and nephrolithiasis can also occur. Topiramate can rarely cause narrow-angle glaucoma, oligohidrosis, and metabolic acidosis.

Pregnancy – Use of topiramate or (especially) valproate during pregnancy has been associated with congenital malformations.32,33

ANTIDEPRESSANTS — Amitriptyline is the only tricyclic antidepressant that has been shown to be effective (off-label) for preventive treatment of migraine,34 but it often causes sedation, dry mouth, and weight gain. Other tricyclics such as nortriptyline, which may have fewer adverse effects, are frequently used as alternatives.

The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) venlafaxine and duloxetine may also be effective in preventing migraine.35,36 Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, sweating, tachycardia, urinary retention, and blood pressure elevations.

CGRP ANTAGONISTS — The long-acting CGRP monoclonal antibodies erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), galcanezumab (Emgality), and eptinezumab (Vyepti) and the oral CGRP receptor antagonists atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec ODT) have reduced the number of migraine days by about 1-2 per month compared to placebo in double-blind trials in patients with episodic or chronic migraine.37-41 CGRP monoclonal antibodies may be effective when other therapies have failed.42-45 No head-to-head comparisons of these drugs are available. Erenumab has been shown (off-label) to be effective for prevention of menstrual migraine.46

Adverse Effects – Injection-site reactions and constipation are the most common adverse effects of CGRP antibodies. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported.47 Erenumab has been associated with hypertension and hair loss.48,49

Systemic adverse effects are uncommon with use of oral CGRP receptor antagonists. Nausea and somnolence can occur. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported with use of rimegepant.

Pregnancy – No adequate data are available on use of CGRP antagonists in pregnant women. Fetal exposure to CGRP antibodies could occur for months after stopping them.

OTHER PREVENTIVE DRUGS — Pericranial intramuscular injections of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) are FDA-approved for preventive treatment of chronic migraine in adults with ≥15 days per month of headaches lasting ≥4 hours.50 Botulinum toxin is not recommended or FDA-approved for prevention of episodic migraine.

NSAIDs, such as naproxen and ibuprofen, have been used to prevent episodic migraine.51 The antihypertensive drugs lisinopril, candesartan, and verapamil have reduced migraine frequency in small studies.52-54

NONPHARMACOLOGIC ACUTE AND PREVENTIVE TREATMENT

DEVICES — Five neuromodulatory devices are FDA-cleared for acute treatment of migraine; four of these are also FDA-cleared for preventive treatment. Some can be used in adolescents as well as adults (see Table 4). These devices have decreased migraine frequency and/or severity compared to sham treatment or historical controls in clinical trials. No trials comparing them to each other or to pharmacologic treatments are available, and experience with their use in clinical practice is limited.1

OTHER INTERVENTIONS — Behavioral interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and biofeedback, and acupuncture have been found to be effective for preventive treatment of migraine, but study quality is mixed.53-57

- J Ailani et al. The American Headache Society consensus statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2021; 61:1021. doi:10.1111/head.14153

- MJ Prior et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acetaminophen for treatment of migraine headache. Headache 2010; 50:819. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01638.x

- CC Suthisisang et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of naproxen sodium in the acute treatment of migraine. Headache 2010; 50:808. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01635.x

- C Suthisisang et al. Efficacy of low-dose ibuprofen in acute migraine treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41:1782. doi:10.1345/aph.1k121

- C Chen et al. Differential pharmacokinetics of diclofenac potassium for oral solution vs immediate-release tablets from a randomized trial: effect of fed and fasting conditions. Headache 2015; 55:265. doi:10.1111/head.12483

- S Alwan et al. Paracetamol use in pregnancy – caution over causal inference from available data. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18:190. doi:10.1038/s41574-021-00606-x

- S Law et al. Sumatriptan plus naproxen for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 4:CD008541. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008541.pub3

- CJ Derry et al. Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults – overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 5:CD009108. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009108.pub2

- G Roberto et al. Triptans and serious adverse vascular events: data mining of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. Cephalalgia 2014; 34:5. doi:10.1177/0333102413499649

- Inhibitors and inducers of CYP enzymes, P-glycoprotein, and other transporters. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023 January 25 (epub). Available at: medicalletter.org/downloads/CYP_PGP_Tables.pdf.

- Y Orlova et al. Association of coprescription of triptan antimigraine drugs and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants with serotonin syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2018; 75:566. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144

- K Nezvalová-Henriksen et al. Triptan safety during pregnancy: a Norwegian population registry study. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28:759. doi:10.1007/s10654-013-9831-x

- US National Library of Medicine. Drugs and Lactation Data-base (LactMed). Available at: https://bit.ly/3MjOzAs. Accessed May 24, 2023.

- Lasmiditan (Reyvow) and ubrogepant (Ubrelvy) for acute treatment of migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2020; 62:35.

- Rimegepant (Nurtec ODT) for acute treatment of migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2020; 62:70.

- Zavegepant (Zavzpret) for acute treatment of migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023 (in press).

- JH VanderPluym et al. Acute treatments for episodic migraine in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2021; 325:2357. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7939

- R Croop et al. Zavegepant nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Headache 2022; 62:1153. doi:10.1111/head.14389

- RB Lipton et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2023; 22:209. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00517-8

- C-P Yang et al. Comparison of new pharmacologic agents with triptans for treatment of migraine: a systemic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2128544. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28544

- TE Baker et al. Human milk and plasma pharmacokinetics of single-dose rimegepant 75 mg in healthy lactating women. Breastfeed Med 2022; 17:277. doi:10.1089/bfm.2021.0250

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Ubrogepant. [Updated 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://bit.ly/43kKnqO. Accessed May 24, 2023.

- MJA Láinez et al. Crossover, double-blind clinical trial comparing almotriptan and ergotamine plus caffeine for acute migraine therapy. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14:269. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01594.x

- SD Silberstein et al. Dihydroergotamine (DHE) – then and now: a narrative review. Headache 2020; 60:40. doi:10.1111/head.13700

- A new dihydroergotamine nasal spray (Trudhesa) for migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2021; 63:204.

- MJ Marmura et al. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache 2015; 55:3. doi:10.1111/head.12499

- JR Saper and AN Da Silva. Medication overuse headache: history, features, prevention and management strategies. CNS Drugs 2013; 27:867. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0081-y

- EA MacGregor et al. Safety and tolerability of frovatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine and prevention of menstrual migraine: results of a new analysis of data from five previously published studies. Gend Med 2010; 7:88. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2010.04.006

- WM Mulleners et al. Antiepileptics in migraine prophylaxis: an updated Cochrane review. Cephalalgia 2015; 35:51. doi:10.1177/0333102414534325

- F Ashtari et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of low-dose topiramate vs propranolol in migraine prophylaxis. Acta Neurol Scand 2008; 118:301. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01087.x

- S Silberstein et al. Topiramate treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quality of life and other efficacy measures. Headache 2009; 49:1153. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01508.x

- In brief: Warning against use of valproate for migraine prevention during pregnancy. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013; 55:45.

- J Weston et al. Monotherapy treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy: congenital malformation outcomes in the child. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 11:CD010224. doi:10.1002/14651858. cd010224.pub2

- JR Couch et al. Amitriptyline in the prophylactic treatment of migraine and chronic daily headache. Headache 2011; 51:33. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01800.x

- S Tarlaci. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009; 32:254. doi:10.1097/wnf.0b013e3181a8c84f

- LB Kisler et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain 2019; 35:753. doi:10.1097/ajp.0000000000000739

- Erenumab (Aimovig) for migraine prevention. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2018; 60:101.

- Fremanezumab (Ajovy) and galcanezumab (Emgality) for migraine prevention. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2018; 60:177.

- Eptinezumab (Vyepti) for migraine prevention. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2020; 62:85.

- Atogepant (Qulipta) for migraine prevention. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2021; 63:169.

- R Croop et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2021; 397:51. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32544-7

- PJ Goadsby et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of erenumab: results from 64 weeks of the LIBERTY study. Neurology 2021; 96:e2724. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000012029

- MD Ferrari et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2019; 394:1030. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31946-4

- DK Kuruppu et al. Efficacy of galcanezumab in patients with migraine who did not benefit from commonly prescribed preventive treatments. BMC Neurol 2021; 21:175. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02196-7

- M Ashina et al. Safety and efficacy of eptinezumab for migraine prevention in patients with two-to-four previous preventive treatment failures (DELIVER): a multi-arm, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol 2022; 21:597. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00185-5

- JM Pavlovic et al. Efficacy and safety of erenumab in women with a history of menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain 2020; 21:95. doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01167-6

- In brief: Erenumab (Aimovig) hypersensitivity. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2019; 61:48.

- In brief: Hypertension with erenumab (Aimovig). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2021; 63:56.

- M Ruiz et al. Alopecia as an emerging adverse event to CGRP monoclonal antibodies: cases series, evaluation of FAERS, and literature review. Cephalalgia 2023; 43:3331024221143538. doi:10.1177/03331024221143538

- Botulinum toxin for chronic migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2011; 53:7.

- S Holland et al. Evidence-based guideline update: NSAIDs and other complementary treatments for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 2012; 78:1346. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182535d0c

- BJ Gales et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for the prevention of migraines. Ann Pharmacother 2010; 44:360. doi:10.1345/aph.1m312

- LJ Stovner et al. A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: a randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study. Cephalalgia 2014; 34:523. doi:10.1177/0333102413515348

- JL Jackson et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0130733. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130733

- J-Y Bae et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for migraine headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021; 58:44. doi:10.3390/medicina58010044

- Y Nestoriuc et al. Biofeedback treatment for headache disorders: a comprehensive efficacy review. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2008; 33:125. doi:10.1007/s10484-008-9060-3

- S-Q Fan et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a trial sequential meta-analysis. J Neurol 2021; 268:4128. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10178-x